"Golf" Ice Cream, Turkey

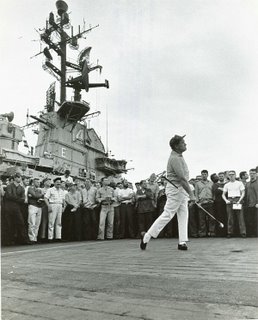

Bob Hope entertaining sailors

off Vietnam

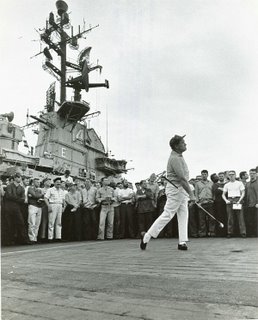

Klassis Golf Club, Turkey

GOLF AND GLOBALIZATIONWhat does golf tell us about globalization?

The game has been something of an American export in the last decades. This began in the Cold War when golf was converted into a strong symbol of the supposed superiority of American capitalism and democracy. If the Communist Russians lived in a dreary black-and-white limbo of cheap vodka, bad borscht and gray Stalinist high rises, we capitalists in the United States cavorted in a shiny Technicolor wonderland of Florida and Arizona golf vacations with blue skies, sparkling white sand, cute electric golf carts, white belts and blue and green polyester plaid pants, and tropical cocktails with little paper umbrellas at the 19th hole. Or so the image-making went.

So many American presidents being golfers has punctuated the connection between the game and the ideology of global American destiny and power. In his goodwill tours entertaining sailors off the coast of Vietnam, comedian Bob Hope hit golf balls from an aircraft carrier deck, the game pushed strangely forward at a bloody frontier of American empire. Along with planting the Stars and Stripes and reading from Genesis, astronaut Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin hit a golf shot on the moon. That memorable moment linked the iconography of nationalism and Christianity with the wacky, boys-will-be-boys American boy fun of hitting a six-iron in zero gravity.

And Tiger Woods, of course, is a child of the Cold War and America’s global entanglements. His Green Beret father Earl never would have met his Thai mother Tida if he hadn’t been sent to fight Communism in Vietnam. The young couple nicknamed their child “Tiger” after a Vietnamese buddy of Earl’s who died in a Hanoi prison camp.

Lately, there’s been increasing talk about golf’s globalization. The PGA would certainly like to have us believe that the sport is taking the world by storm – with the accompanying fortune in yen, yuan, and Euros to be made from “worldwiding” its product. One golf world, linked by the miracle of television and creating vast new markets for balls, clubs, cable channels, licensing rights, and the rest. It’s a dream being pursued by Tim Finchem and vigorous corporate golf interests from course architects to equipment makers and resort companies.

But like globalization itself, the realities of golf’s spread are strange, uneven, and not always according to plan. I’m teaching this fall in Turkey. It’s a country of almost one hundred million people with a big, expanding economy and famously strategic location at Europe and Asia’s crossroads. You’d think that golf would be taking off here. The Turkish Golf Federation has energetically promoted the game, including school outreach that provided the young core of Turkey’s recent European Club championship-winning team. And the requisite originary nationalist myth is even in place. According to this story, modern Turkey’s founder, Mustafa Kemal, once visited the country’s first golf course, the Istanbul Golf Club, and was served coffee and cognac there by the course manager’s son. The great man supposedly instructed the boy “to study and learn golf for the benefit of Turkey.” Mustafa Kemal died in 1938, but the cult of personality to Ataturk (“The Father of the Turks”), as he became known, must be the largest to any single world leader, dead or alive; it outstrips the lionization of Fidel Castro in Cuba or Kim Jong Il in North Korea, more like the nationalist necrophilia of Lenin’s Tomb or the older monumentalization of Egyptian Pharoahs and Roman Emperors. Ataturk’s picture is literally everywhere in Turkey. His real or imagined endorsement of golf provides necessary official certification in this country that takes its nationalism and great nationalist hero with absolute unironic seriousness.

But Turkey still has only about three thousand golfers. And only about ten courses. Ambitious plans to expand that number to a hundred have run into opposition. Recently, an environmentalist coalition called the Sorgun Platform forced the cancellation of a planned course that would have required cutting down old-growth forest along Turkey’s Mediterranean Coast. They weren’t swayed by the Turkish Minister of Tourism’s insistence that the planned course would actually protect forest by preventing forest fires. In that case, why not cut down all Turkey’s trees, the Sorgun activists sarcastically suggested?

Here golf is also invisible on that ubiquitous postmodern Delphic oracle, television. The NBA has done wonders in forcing its way onto Turkish screens. Several channels carry both this season’s contests and grainy old vintage match-ups. Many Turks recognize LeBron James, Kobe Bryant, and other NBA stars. Tiger Woods? He’s conspicuous by his invisibility on television and other Turkish media. Tiger might be an obscure bench-warmer for the Sacramento Kings for all that Turks know or care about him. One of the most popular Turkish ice cream brands is called “Golf.” But the name appears to be just an empty marker of the modern, the cosmopolitan, and the Western – like the knock-off t-shirts you see here with stray nonsensical English words like “Force,” “Foxy” or “Wavelength.” I suspect many locals buying popsicles don’t know, or care, what “Golf” means.

Why hasn’t golf taken hold here? Economics is one reason. Unlike soccer, basketball, or baseball, golf is not played by poor people anywhere in the world. The cost – green fees and equipment, even in their cheapest versions – prevents it. And thus the pattern to golf globalization; the sport has spread in countries with robust, developed economies of the northern hemisphere. That includes Asian nations like Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea as well as European ones like Spain, Sweden, Germany, and England together, of course, with the United States. You must have big, relatively affluent middle class for golf to take hold.

Turkey’s middle-class is growing, and yet it’s still a poor country relative to global capitalism’s success stories. And other obstacles exist – a lack of space for courses in vastly overcrowded Istanbul; the absence of a charismatic Turkish player to spark interest; the relative segregation of gender roles that tends to discourage female sports participation. As in, say, Brazil or Peru, golf in Turkey is an elite enclave sport played on fenced in courses designed to keep out the poor and the lower classes. Here the rich and the visiting foreign businessmen live in their own partitioned society of fancy sedans and SUVs, credit cards and jet travel, and the luxury of being waited on by others The world is not flat contrary to what any simple celebration of globalization would have us believe. And golf exemplifies division, exclusion and the ugly contrasts between the haves and have nots so much a part of globalization’s advance.

I visited the Klassis Country Club outside Istanbul a few weeks ago. It’s a quite beautiful, hilly course designed partly by Tony Jacklin; it looked especially striking with the frost and gold and brown leaves that reminded me of the Italy’s Appenines in the fall. But a round here and the required cart cost the equivalent of well over one hundred dollars, a week’s salary for the average Turk. There was only a group of Japanese businessmen out golfing on this cold November day; a few Bulgarians come down as the border is close and Bulgaria has no good course; and Swedes make up the largest percentage of the club’s foreign golf tourists (and golf’s rise in Sweden has been remarkable to the point that some 900,000 people there, a tenth of the population, play the game). These visitors and some wealthy Turks comprise the Klassis clientele. The course is surrounded by a barbed wire fence to keep out local villagers who graze their sheep nearby.

Maybe golf will eventually break through in Turkey. But for now the action is elsewhere – and perhaps most intriguingly in China. Both Bill Clinton and Tiger Woods have made recent golf-promoting visits there with Tiger playing in the Shanghai Open. The image of golf as linked to globalization from above, the excesses of savage capitalism, and the decadent West has been an obstacle to expansion in the world’s most populous country. Peking University just cancelled plans to build a practice putting green in response to complaints that a rich man’s sport has no place in a country with so much poverty.

But, as China’s professional classes grow, it seems inevitable that golf will as well, and golf and capitalist expansion going hand-in-hand as they always have.

A day after the news from Peking University, another newspaper reported that Xiamen University just made golf a required class for economics and computer software majors.

Playing the game, a professor there said, would “improve their job prospects.”